6. March 19, 2023

Beginnings in China. "No Name Woman"/ "No Name Country," Taiwan. "THINK PEACE" with Liya Yu.

My maternal grandmother died in 1990, at the end of the first semester of my last year of high school, when the opening paragraphs of a single book in the East Asian history class newly introduced to the school I’d been attending for twelve years in New York City, changed my life. Maxine Hong Kingston’s “The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts,” grabbed me and mystified me at the same time. I simultaneously knew why, the Chinese language, the history, the culture of three generations of women in one family were calling me, but I could not yet articulate or understand the layers of complexity behind the why — and closing that gap would draw me in for the rest of my life and bring me to now.

“You must not tell anyone what I am about to tell you.”

That fiercely whispered warning comes from Kingston’s mother and opens her book. Her mother is about to tell an adolescent Maxine an intensely private, cautionary tale, intended only for her. I had been there in exactly Maxine’s position with my own mother as a girl. That Kingston starts her memoir this way and then shares the secret story, meant that this book would involve the breaking of taboos. I was riveted.

What story is so dangerous that Maxine Hong Kingston must not speak about it? It’s the tale of the “No Name Woman,” Maxine’s aunt, her father’s sister, who stayed in China while her husband went to the United States to work. After he had been gone for years, her aunt became pregnant – but there was no husband to be the baby’s father in China. Her family and the villagers were so dishonored by what they believed to be her aunt’s adultery that they shamed, shunned, and humiliated her, destroying her family home as punishment. The man who impregnated her also partook in the carnage rather than taking responsibility. After giving birth in a pigsty, Maxine’s aunt was so distraught that she drowned herself and her baby in the well. The family never spoke her name again and resolved to forget she ever existed.

That is the opening of Maxine Hong Kingston’s book. I knew my mother’s and my grandmother’s secrets were embedded in such a story of an overwhelmingly injustice, an unspeakable violence — an injustice so powerful and so brutal it would kill you if it could or settle for silencing and erasing you while you were alive, a living death.

The you was gendered. It was mothers. It was aunts. It was grandmothers. It was me. And Kingston knew it. She focused on three generations of women in her family in China and America. It was a revelation to me to honor their stories this way and break the silence around their injustice that they themselves were drowning in.

When my mother handed her story and her mother’s story to me, I could see the fear in her eyes and feel the grief that their stories could never be told or understood in a way this world would hear and honor. I know now that this is called “epistemic injustice” and that it has been happening to women since ancient times as Mary Beard has written about in her slim volume, “Women & Power.” I knew then that my mother wanted to protect me from ever experiencing what had happened to her and to my grandmother. I felt her both cautioning me not to be crushed by the overwhelming injustice done to women and conferring on me the assignment of figuring out how to break her free, break my grandmother free, and break women free. Maybe I also took the assignment on myself. The woman warrior was certainly a title I liked.

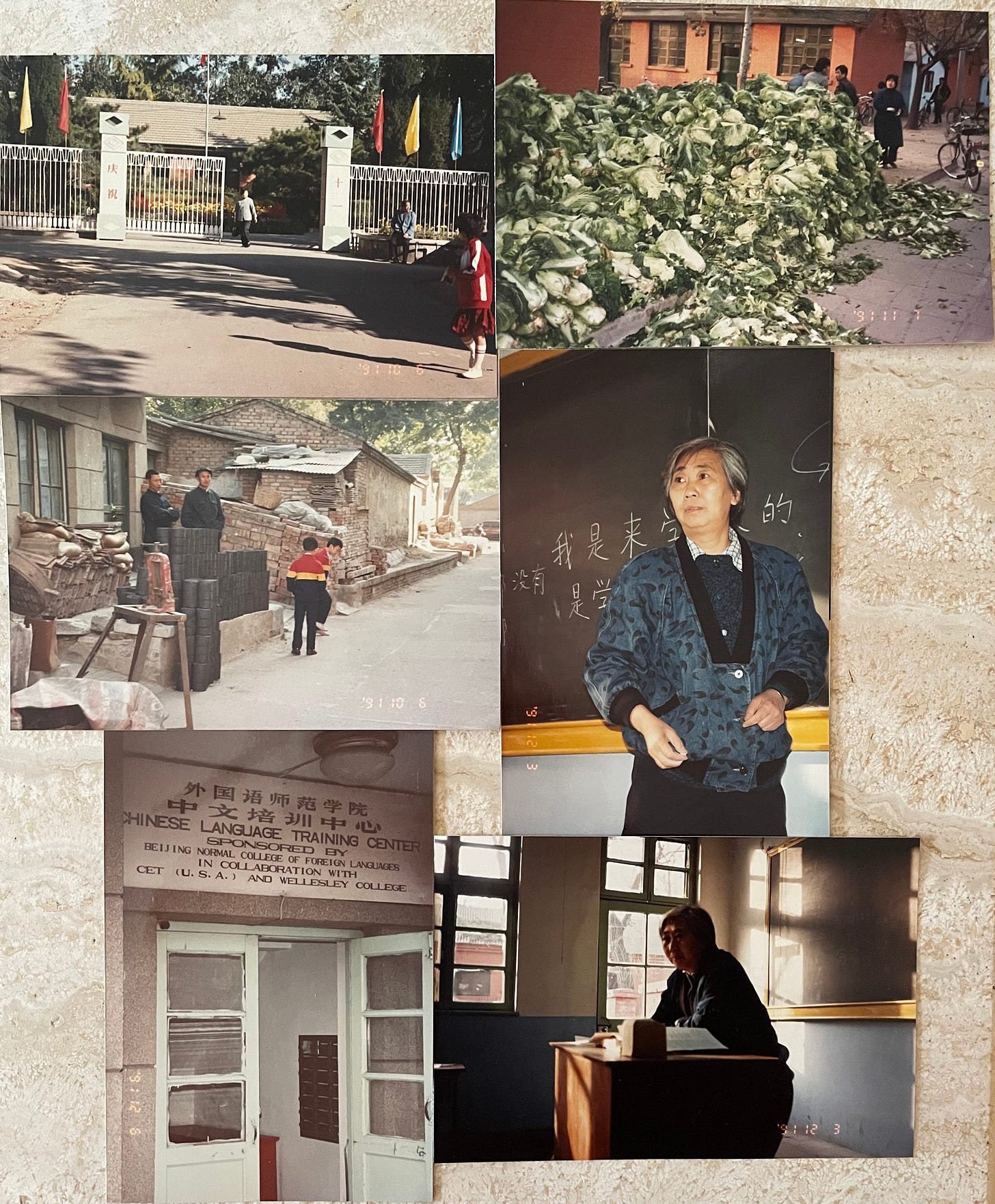

And then, just as Kingston had not yet been to China when she wrote her memoir about her mother’s and her grandmother’s generations, though she went afterward, so I was moved after reading her memoir to travel to China at eighteen in 1991. It was my first semester of college. I was the youngest person on this study abroad program, China Educational Tours (C.E.T.), and one of only a handful of Americans in Beijing at that time. (See this graph on Americans studying in China through the decades. Most choose Europe.) I’ve been studying Chinese, China and Taiwan, living and working in both places through the years ever since.

What I encountered in Beijing in 1991 was people who had known unspeakable violence. It felt like a land silenced by an unspeakable terror because it was. It was full of people still terrified, weary, distrustful. The city was quiet, grey, mostly shut down and a little grim. There were dirt roads and hutongs I biked and walked through. Uyghur food stalls of hanging roasted meat just outside the school walls. I loved the smell of burning coal, unfortunately, and the site of walls of bright green cabbage, dumped from the backs of farm trucks, piled high on the sidewalks in winter. I loved my Chinese language teacher. I could feel the city opening up to some vague promise of new possibilities on a distant horizon. Maybe by our very presence in Beijing at that time, our motley group of less than thirty foreign students from the North and South of the U.S., from France and from Germany, offered early, timid connections to an outside world of hope.

That every Beijinger I met was so obviously hiding truths, and not speaking about the pain they were hiding made it more painful and sad. This was only two and a half years after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, and I had not seen it on TV. I had almost no understanding at that time of what had gone on. I remember particular classmates from a course on the history of communism running down the halls of my high school and talking about the fall of the Berlin Wall and the break up of the Soviet Union. But there was not yet and had never been a course on East Asia in the history of the school until the one I took a year later. No one had talked to me about the Tiananmen massacre in depth before I went to China. No one could have prepared me. I did not have a clue what I was getting into.

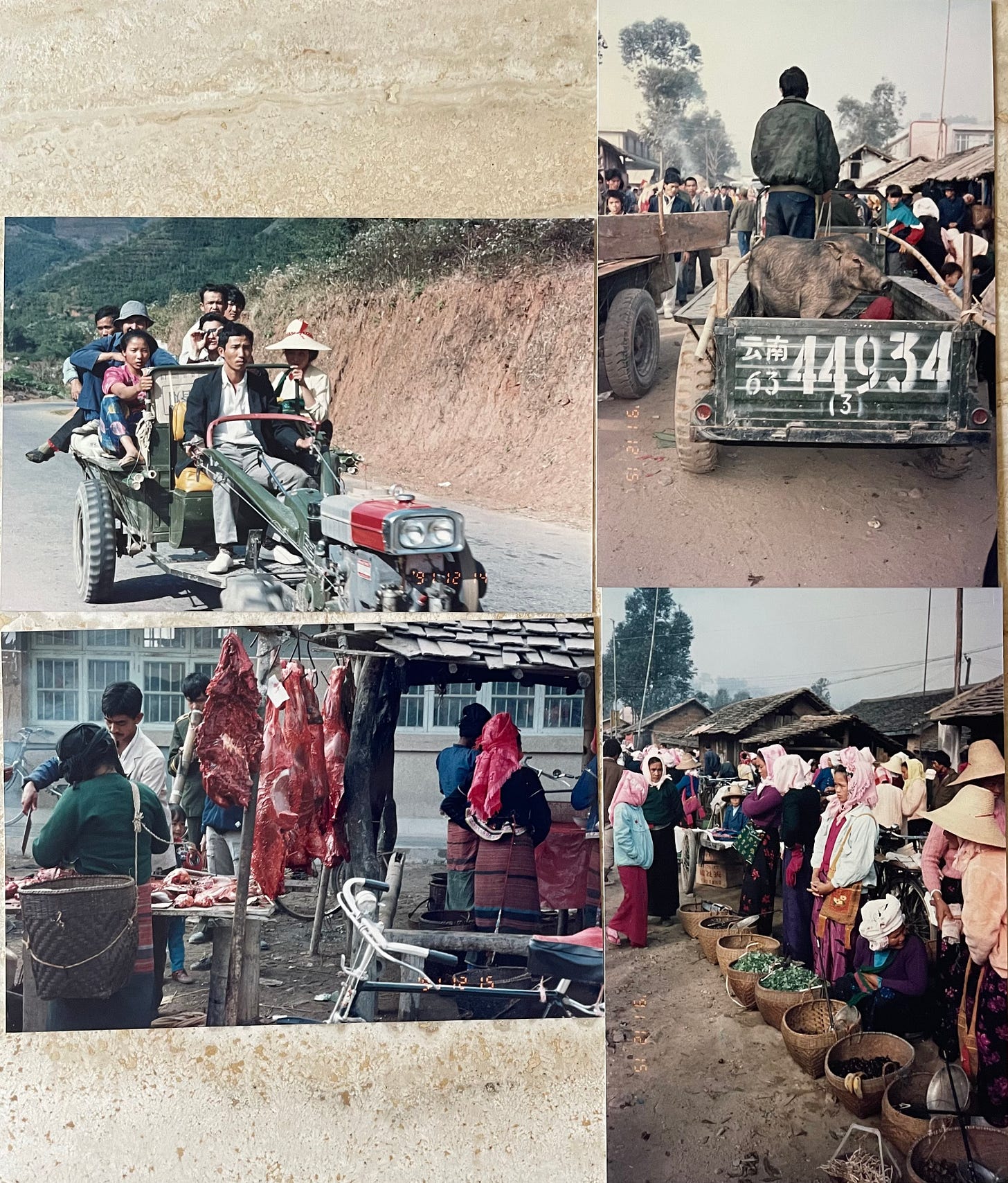

It was a violence that literally could not be spoken because the state would not allow it. It was a fear and a grief I recognized from my mother’s eyes that I could see in my Chinese friends’ eyes and feel weighing heavily on those few I was allowed to meet through orchestrated and coordinated efforts to control and guide my understanding of this city and country. I taught English. I dug ditches on Joan Hinton’s dairy farm. I was invited for tea at my pre-arranged friend’s house where they showed me giant photo albums of their travels through China and declared their patriotic love for their country and lack of desire to see any other forbidden part of the world. I met Zhang Daxing who showed us Potemkin villages of happy peasants making dumplings and CCP work meetings full of smiling faces. I was cast in a commercial for what I don’t remember, with my friend Pauline J. Yao. I traveled to Yunnan province in the South, to the rice fields and mountains of Kunming and Dali which were stunningly beautiful.

I knew I was in a closed world being shown a more closed world, and that there was far more going on above and below the surface than was meeting my teenage eyes.

Once I feel an emotional connection and commit to a seemingly insurmountable set of challenges, I go deep. And I don’t give up on people whether they’ve been hurt and unconsciously hurt others, dehumanized or discriminated against and unconsciously or consciously exclude or dehumanize or discriminate against others, whether they have hurt me or not. (Ted wants me to better protect myself from taking on other people’s pain and believing in them without a bottom line. I’m trying, but usually I need help from him and friends to enforce a boundary.)

Sometimes, the seeming insurmountability of a challenge will stymie me, but rather than push head on against that brick wall, I have learned to redirect, go with a new flow, like water, only to return to the same challenge from a new angle and break through. It helps to see Taiwan from China’s perspective and China from Taiwan’s perspective. It helps to see both from the US’s perspective and China’s and Taiwan’s perspectives on the US. And just as that first East Asian history class I took also included Japan and Korea, so I look forward to learning more about their perspectives. To begin to know China and Taiwan takes passion, patience, trust, study, listening, openness (caution on the openness!), sincerity, endurance, time, attention and love.

I’ll never forget one of the interviews I shot for my last documentary on the US-China relationship under President Obama that did not make the cut. I will keep this post-college graduate working in Beijing nameless, but I filmed him outside, on the back patio of a cafe at night in Sanlitun around 2012. There was bamboo behind him acting as a barrier to the sidewalk that we lit along with his face. He could not possibly have looked more sinister (not intentional on our part) or sounded more ruthless and conniving when in all his American privilege with all his advantages of free speech, freedom of the press, rights, education, and a cushy, suburban life, after expressing sexist disdain for his mother holding back his greatness by having something of a life of her own, he explained to me what documentarian Sue Williams’ problem was and how simple it was to solve.

“Just cut the Tiananmen square sequence from her film!” he stated bluntly about the woman who has singlehandedly documented through archival film more of China’s history than any other American. “It’s that simple. Then it will be shown in China. What’s the big deal!? We all do it. We all know what to say and what not to say to get along and get ahead in China. It’s so easy. The three Ts: Tibet, Tiananmen, Taiwan. Avoid them. She’s such a fool for not complying.”

There it was. The “Chimerica” bargain in full force two decades after my first time in China (when few were there to exploit anyone or anything). Go along with the lies. Make light of the lies. Play the lie and jump the line. Get ahead. Make your money. Profit over people. Personal ambition over community. Dead bodies piled up then or in the future be damned. Deliberately hide or twist the truth, rewrite the past to erase the truth and preserve your own power and financial access and that of China’s communist party. Censor yourself and others. Silence yourself and others. If anyone, or more importantly, any company that is not forced to parrot the CCP’s lines because they were born in China or have no other choice but to live and work in China, parrots CCP lines and thinks they’re successfully fooling people, winning at the game, getting themselves ahead, getting China ahead and not hurting people, they’re wrong. They’re hurting people and their bottom line if it isn’t already China’s red lines: Tiananmen, Tibet, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, persecuted lawyers, booksellers, writers, artists, workers, farmers, filmmakers, scientists, then their bottom line, which shouldn’t be money, should be violence against Taiwan.

“You’re an empath,” my friend Liya Yu offered as we sat at a table looking out through the floor to ceiling glass wall of a restaurant in Taipei where we were having breakfast and trading stories. I took it as high praise from the woman who has written a new book about “The Neuropolitics of Divided Societies” and what can bring people together. “How do you make people feel seen and heard? When you feel seen and heard, you just breathe, your whole body doesn’t have to hold up any armor. You’ve been validated,” Liya shared in interview on a podcast called “Think Peace” that I’d listened to before we met. What she describes is, to me, the difference between what it feels like living in Taiwan where honesty, transparency and openness abound vs China and Hollywood where lies, manipulation and deception are everywhere from everyone at every turn except behind closed doors.

Liya Yu’s own personal history straddles China and Germany and she approaches politics, she says, “from the viewpoint of catastrophe and fragility.” Her parents survived Maoist China and the Cultural Revolution, and a Germany coming out of Naziism, of fascism. These were catastrophic events of the 20th century where whole political orders collapsed. Liya believes that if racism, colonialism and sexism are acts of radical exclusion then the only way to get back in is to be part of redefining what it is to be human and what is the good political life.

“There’s less polarization than we think,” she shared, “but there’s a big exhausted middle. If a lot of people are on the fence because they don’t think racism or slavery or women’s oppression are good, but they feel threatened by people of all races and genders needing equality, then it’s a chance and a challenge.” We have to “pitch the social contract anew and include a political interest in it for people.” We need to help people understand that, “If you don’t humanize others then the world will be less safe, there will be less cooperation, more violence and you will lose out.” Shaming is strong, but it doesn’t achieve enough. “It’s too naive,” Liya argues. You need people to be politically motivated to feel there’s a social contract there for them, a bigger project.

Shawna Yang Ryan’s piece “On Taiwan and Refusing to Stay Silent” brought all of this back to me as she opens with Maxine Hong Kingston and connects her words to how Taiwan is framed in China and America. “No Name Woman,” is “No Name Country” is Taiwan if we’re not careful and paying international attention to its predicament.

Once you grasp the profundity of Kingston’s memoir, its truths appear everywhere. She unlocks the secrets of the patriarchy, shows us how to unravel its knot and be part of a bigger project against violence in the family, the state, and the world.

Lu captured my thoughts and sentiments exactly.

Fascinating and inspiring to read- can’t wait for you to dive into 1991!

Wow, Vanessa, this is heartbreaking and insightful. Thank you for sharing both the personal and the political, and for connecting the dots between them.